It came unexpectedly — a virus that impacted millions worldwide, killing over 282,000 individuals in America alone. Though the COVID-19 pandemic and its dangers are far from over, colleges and universities reopened their doors for the fall semester and plan on staying open through the spring when students return from the winter break holidays. For college towns like Boston, this means welcoming a second wave of thousands of young adults back from across the globe — right as the pandemic is cresting. Many schools enacted protocols meant to keep their students safe around campus this fall — but will that be enough to quell the spread of the virus when they come back in January? Or are schools setting themselves up for a shutdown?

When determining if college students should return to Boston, institutions in conjunction with state officials had to consider both the health and economic impact of students returning to campus. The Federal Reserve of Boston states that 19 cities in the region of New England rely heavily on financially vulnerable colleges — meaning that with less students and visitors, local businesses might be forced to shut down. This might contribute to an economic downturn as tax revenues drop.

After peaking in April, the number of cases in Boston slowly declined as the city remained in lockdown. In the summer, Boston seemed to have the virus more under control than other cities. However, with many schools back in session and state regulations loosening, Boston has experienced a significant spike in cases and hospitalizations. That corresponds to a second wave of the coronavirus in the U.S., with cities nationwide experiencing the highest numbers of cases that they have seen to date.

The reality of college outbreaks

Although colleges have invested heavily in reopening, their efforts have not been foolproof as there have been several campus outbreaks.

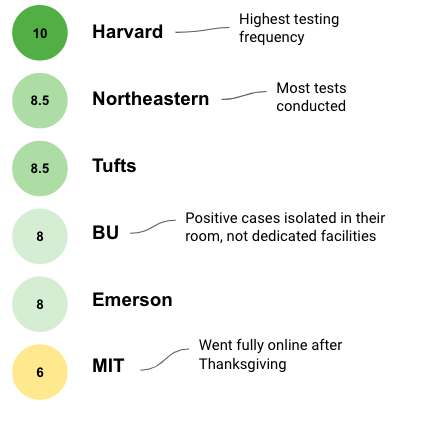

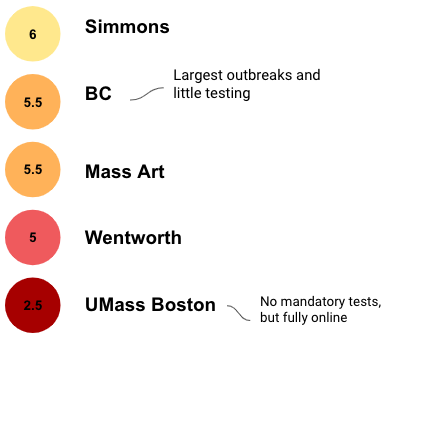

At Boston College, over the Labor Day weekend, 73 students tested positive for coronavirus, giving the college a positive rate of 2.46 percent, which was higher at the time than all of Massachusetts. Some students blamed the administration which conducted no asymptomatic testing and have provided little communication amongst its students. Through Oct. 29, a total of 249 positive cases were recorded at the college.

“The policies that they have in place for coronavirus are unclear and subjective,” said one student who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals. “The Office of Student Affairs has done an extremely poor job in response to coronavirus violations and students. They have given unreasonable and harsh punishments [...] and do not seem to care about students' mental health or academics.”

Similarly, at Boston University during the week of Oct. 11, 20 students and 10 staff tested positive. The cases then remained at a high for several days. In response to the outbreak, BU tightened its restriction on campus public spaces and required students to have proof of testing compliance and no symptoms with their “attestation badges.” President Robert A. Brown and Kenneth Elmore, associate provost and dean of students, attributed the outbreak to the increase of indoor meetings with the cold weather and students disregarding university protocol due to few positive cases.

Northeastern also experienced a considerable increase in positive cases for both students and faculty following Halloween. After a small outbreak among dining hall employees in Stetson East, one of Northeastern’s on-campus dining facilities, the school is experiencing the highest percentages of positive cases since reopening. While the guidelines on campus have only eased slightly, to allow students in dorms to have one guest from their building visit their room, this could have also been a contributing factor. Northeastern has been consistently experiencing extremely low numbers of cases, especially in comparison to some of the other schools in the area.

What measures are being taken?

Hybrid class models give students an option to take classes remotely or in person; this measure halved class capacity and reduced student population density on campus as many students decide to take classes from home.

Additionally, all colleges in the Boston area have imposed basic coronavirus prevention guidelines: social distancing, mask wearing, personal hygiene, and restrictions on social gatherings. This has limited student’s ability to take part in organizations, encouraging clubs who wish to remain in session during the semester to adopt a virtual format.

Most schools have also enforced testing policies for students on campus. When students arrive on campus after travelling, they are required to quarantine anywhere from two days up to two weeks. Students are also subject to regular testing thereafter to monitor their health and control the spread. The practice of regularly testing all students was not adopted by smaller colleges that only test students with symptoms or those at risk, perhaps due to a lack of budget or infrastructure to support in-house testing and results processing.

How are schools enforcing these measures?

While student bodies across Boston have quickly adjusted to this new normal, some schools have already punished students who have broken protocol.

In early September, Northeastern dismissed 11 students at the Westin Hotel near campus for violating social-distancing guidelines outlined by the school. The students returned home and were refunded the tuition cost after legal disputes with the school.

Northeastern Univ. has kicked out 11 students for gathering in a hotel room. And, they still have to pay full tuition.

— CNN (@CNN) September 7, 2020

"A lot of people feel for the students in that they still have to pay the tuition when the semester has not even started," says @kellycatchan of @HuntNewsNU. pic.twitter.com/nN9sZwE6aA

This decision by the school sparked significant outcry amongst Northeastern students, and was the first punishment executed by the university — or any university in Boston — because of a violation of their coronavirus protocol.

Boston University soon followed by suspending 12 of its students after finding they had violated safeguards by partying without social-distancing and mask-wearing. BU’s enforcement of their guidelines also came at a time when the school had experienced a drastic uptick in cases across campus.

What do students have to say about the reopening?

A survey of 240 students from colleges in Boston on their college experience found that around 80 percent of students felt relatively safe being on campus and that their schools’ procedures were effective in preventing and dealing with the virus.

For colleges with in-person class options, about 82 percent of students felt willing to go to in-person classes in some capacity while only 28 percent felt that their tuition cost matched the quality of education this semester. Although the majority of students indicated that they were satisfied with the safety of schools and their coronavirus resources, there is still noticeable resentment for the perceived overpriced tuition and limited on-campus experience schools have offered.

“While Wentworth has been good about their pandemic handling,” said one student who requested anonymity. “The education I've been receiving is not nearly as good as it could be. At all.”

For schools such as Emerson College and Berklee College of Music — both institutions of the arts — students express that they are happy to be “back on campus,” but say the quality of their education has decreased due to the restrictions placed on in-person classes. For these students, the college experience includes being surrounded by “like-minded musicians and creatives, and to be involved in the Boston music scene,” as one Berklee student stated, which has been difficult to replicate on an online platform.

Several survey responses indicated that students were “grateful for having some in-person opportunities” and appreciated “how hard their administrators are working to make the semester work.” On the other hand, students tend to be more critical at colleges that have had recent outbreaks or have not planned remote education extensively.

What do the numbers show?

Testing frequency appears to have a significant impact on cases: as the number administered per week increases, the percentage of positive results declines. UMass Boston, which does not have mandatory testing, has the highest rate of positivity at 0.8 percent while Northeastern, which tests twice a week, has a positivity rate of 0.1 percent. Frequent testing can give more timely insight into virus trends and thus affect policies and measures in place to better protect students and avoid outbreaks.

Overall, it was found that no aspects of a university’s student body composition and funding could help control the spread. Safety comes from measures such as proper social distancing, strict quarantine policies for students arriving on campus, willingness of students to stay safe, and –most importantly– access to regular testing.

The experts' take on the importance of testing

That conclusion is echoed by Paul Beninger, an associate professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts University.

Testing can help “paint a picture of what is going on and find patterns,” said Beninger.He cautions that testing does not work if not done frequently and at a high rate.

“Testing weekly is obsolete,” said Beninger. “You’re doomed because you are always going to be a week behind.”

Beninger emphasized that schools should decentralize their policy making. “It is more valuable to devolve decision making when things are changing quickly on the ground and you don’t know a lot,” Beninger said. “The biggest problem with centralization is everyone sits around waiting for an authority to make a central decision.”

Northeastern, which took a centralized approach towards the pandemic, was criticized by Beninger for their long list of policies to try to minimize the spread of coronavirus on their campus. “Northeastern’s list is undoable. It is a great reference, but the problem is they will have to change those things almost daily or weekly because things are constantly changing.”

Which school is safe then?

The Center for Disease Control recommends four requirements all schools should consider when opening up during the pandemic. They recommend that schools should “promote behaviors that reduce the spread of coronavirus, maintain healthy environments, maintain healthy operations, and prepare for when someone gets sick.”

Using this CDC guideline for the reopening of schools, we determined a grading scale for each college or university that is scored out of ten points. This scale looks at four main criteria: testing frequency, availability of on campus dedicated isolation facilities, learning modality (e.g. in person, fully remote, or hybrid), and shortened academic calendars around main holidays.

Harvard scored best due to its high frequency testing, campus capacity of 40 percent and mostly online classes. UMass Boston scored worst because, although fully online, students have gone back to campus where testing is not mandatory, there are no separate isolation facilities, and semesters have not been shortened to decrease campus density around main holidays.

Plans for the Spring Semester? To each their own!

As colleges and universities across Boston begin to wrap up their fall semesters, many are planning for the spring semester. For the most part, these are similar to the fall guidelines, with almost every school choosing to extend their winter break by delaying the start of their spring semester.

Northeastern’s hybrid model NUFlex will be extended to the spring semester. In early October, the administration also announced that it would be beginning the semester one week later than usual, in addition to cancelling the school’s spring break in early March. The university intends to continue its coronavirus guidelines from the previous semester.

ANNOUNCEMENT: Berklee College of Music and @BosConservatory at Berklee will reopen their Boston campus facilities in January 2021 with a hybrid model, blending remote and on-campus teaching. To learn more, visit https://t.co/VRBFI8Ksd3. #SpringBackToBerklee pic.twitter.com/6PTsFeKL7f

— Berklee (@BerkleeCollege) October 15, 2020

Some schools, however, plan to take the next step from plans they followed in the fall. Berklee, which had their students learning remotely this fall, plans to welcome back its students through their hybrid model “Spring Back to Berklee.” The semester will begin on Jan. 25 and will also not feature a spring break.

Tufts University will begin its spring semester the latest, with the administration planning to start class instruction on Feb. 1. Instead of cancelling spring break altogether, the university has instead shortened it to a long weekend, advising students who are in-person not to travel during this time.

Looking forward

As the current situation develops, schools seem to be adapting to changing conditions. Over the course of these past few months, they’ve created a new normal of online classes, restricted gatherings, and continuous testing by funding research centers. Priorities were set to preserve health and safety, but this might have reflected negatively on students’ mental health and satisfaction.

Many universities have now shortened their fall semesters, a measure aimed at avoiding outbreaks after the holidays, while others remain true to a traditional calendar, but maintain strict testing policies. This practice has single handedly been the most effective measure in controlling the spread within campuses and has kept positivity rates well below those of Massachusetts. Yet, many institutions that are not testing regularly have still not changed this practice to follow the evidence that testing is the most effective measure against coronavirus.

One thing still remains to be seen, how well will colleges cope with a new wave of students returning to campus in January? The situation now is much worse than it was in August, how will colleges adapt arrival and testing policies? Will they be able to keep their safety bubbles intact as students return from all across the globe?